Yoga Anatomy: Different Types of Forward Head Posture and How to Work with Them

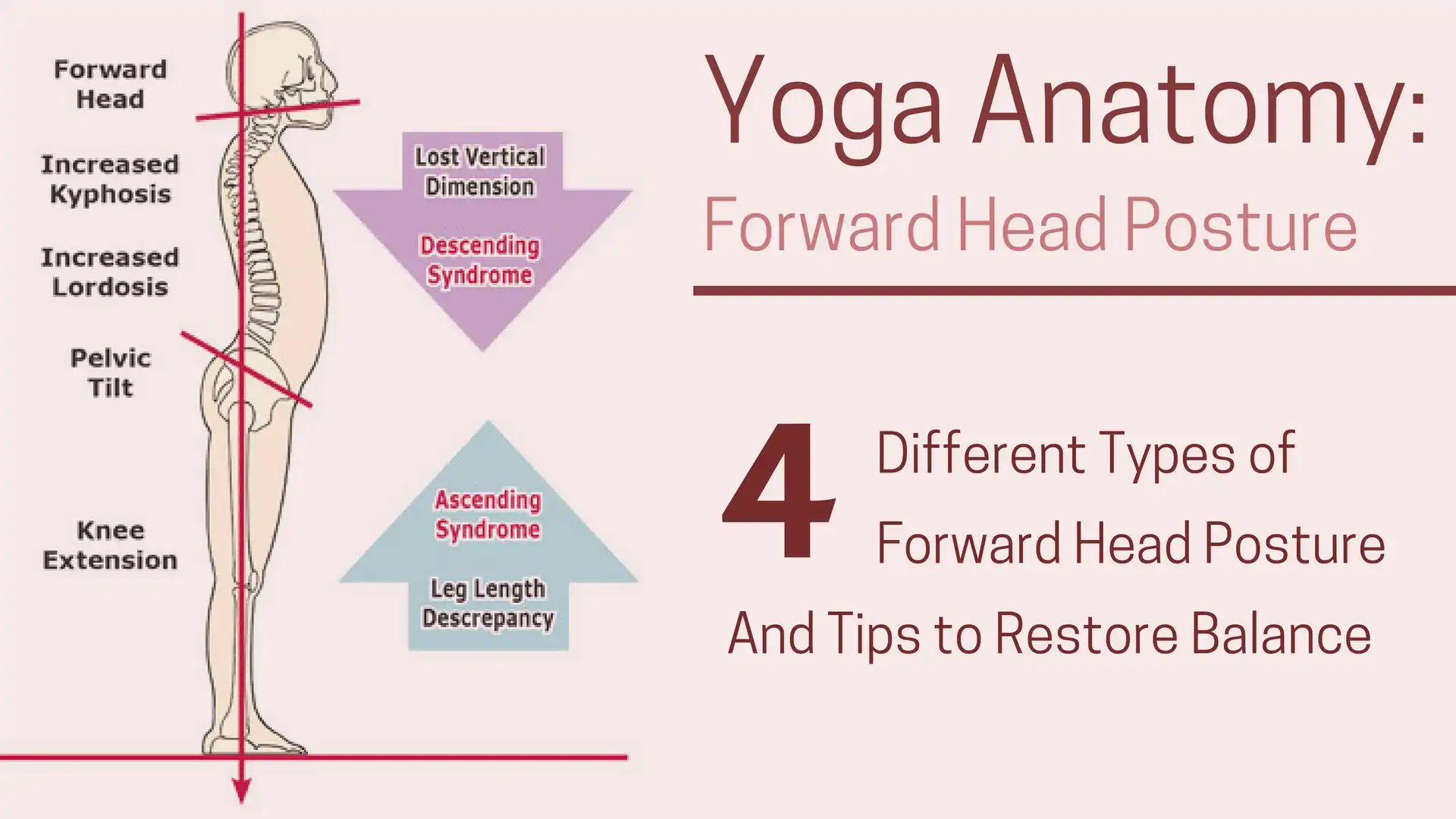

Often seen as a structurally subtle body segment, the neck is burdened with the challenging task of supporting and moving the human head. Because of the tension, trauma and poor postural habits inherent in today’s workplace, it is no surprise that head-on-neck and neck-on-thorax disorders rank high among the most common pain generators driving people into bodywork and movement practices.

How Yoga Can Help

Yoga, when practiced with alignment in mind, can help change poor postural habits. Yoga poses that counter the forward-bending patterns of desk work can help unwind forward head patterns. Practicing Tadasana (Mountain Pose) with alignment awareness is a good first step. You can then transfer Tadasana’s alignment principles into other asanas—and beyond. Try “sitting” in Tadasana at your desk. Instead of grounding your feet, ground your pelvis, then lift your sternum, draw your head back so that the ears align with the shoulders. You may need to place your computer up higher so that you don’t have to look down at the screen.

Also, take short asana breaks every 20-30 minutes. Talasana (Palm Tree Pose) and “Desk” Dog (placing your hands on your desk, bending forward and stretching your hips back) are good options.

Poses such as Supported Matsyasana (Fish Pose) on blocks can help relax anterior chest and shoulder muscles. Salamba Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Supported Bridge Pose) expands the chest while simultaneously releasing tension in the posterior neck muscles. Spinal rotations (twists) and lateral bends such as Talasana (Palm Tree Pose), help to mobilize the thoracic area.

In addition, if you are an advanced yoga practitioner, yoga teacher, or body worker, you may find inspiration for working with forward head posture in your practice in this writeup by renowned body worker Erick Dalton. Dalton describes four types of neck imbalances related to forward head posture and how to work with them using body work methods.

This two-part series is excerpted from the author’s textbook, Advanced Myoskeletal Techniques. Part One examined the causes, conditions, and corrections for one of the most prevalent and painful of all structural disorders: forward-head postures. In this issue, common neck pathologies will be reviewed with special focus on the age-old “straight-neck” controversy and related conditions such as osteoarthritis, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction and Dowager’s hump.

The Physiology of Muscle Imbalances: Altered Length-Tension Imbalances and How to Work with Them

In the early 1900s, Sir Charles Scott Sherrington, an English physiologist and Nobel Prize recipient, first described the neurological concept of reciprocal innervation. Simply stated, if a muscle receives a nerve impulse to contract, its antagonist simultaneously receives a nerve impulse to relax. Sherrington’s Law of Reciprocal Inhibition further describes how one muscle group neurologically weakens when length-tension imbalance occurs to paired antagonists; i.e., tight pectorals overpowering and reciprocally weakening rhomboid major and lower trapezius. But why do these substitution patterns develop? Altered length-tension imbalance patterns typically result from faulty posture, gravitational stress, repetitive movement, cumulative trauma, and loss of neuromuscular control.

Synergistic dominance may be defined as “acting together; enhancing the effect of another force.” Therefore, if muscles perform the same task at a particular joint, they are termed synergistic. Synergistic dominance occurs as “helper” muscles are recruited to take over function when a “prime mover” muscle fails, much like when a football coach calls in the substitute players when a key player is injured. Synergistic stabilizers are designed to help but not be primary contributors to a particular movement.

Figure 1: Suboccipital receptor release. To co-activate Golgi receptors and stretch suboccipitals, the therapist flexes the client’s head on thumb and searches for fibrosis and myospasm along the occipital ridge. If adhesive tissue is palpated, the client is asked to inhale and gently hyperextend his head against the therapist’s resistance to a count of five. The client exhales and the therapist’s thumb pressure produces a post isometric and Golgi receptor release of the suboccipitals.

Figure 2: SCM receptor release. The sidelying client raises his head and rotates toward the table to expose the SCM muscle belly. The therapist’s soft finger pads hook the SCM as the client continues left head rotation against the therapist’s resistance until a Golgi tendon release is experienced. The client controls the amount of available stretch by increasing left head rotation. No pulse should be felt during this technique.

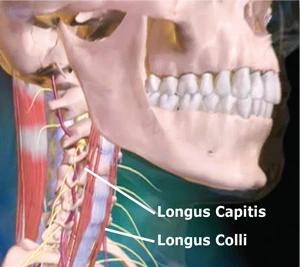

Head-raise test

Forward bending of the head and neck with the client in a supine position should initiate the following firing-order sequence: longus capitis, longus colli, anterior scalenes, and sternocleidomastoids. The deepest intrinsic muscles must fire first starting with longus capitis flexing the head on the neck followed by longus colli initiating the beginning of neck flexion. Anterior scalenes and sternocleidomastoids can then join forces to produce smooth head-and-neck flexion. The most commonly seen substitution pattern (sternocleidomastoids, anterior scalenes, longus colli, and longus capitis) causes the chin to reach toward the ceiling rather than tucking into the chest during the first two inches of flexion efforts (Figure 4) (below).

The head-raise test alerts the therapist as to which muscles need lengthening and which must be tonified. Tension-length imbalances are usually easy to fix, as the therapist’s fingers, elbows and fists release and separate muscle adhesions and contractures allowing fascial bags to glide freely on neighboring structures. By performing the head-raise test before and after each neck session, aberrant substitution patterns can be easily identified and corrected. Therapists will discover greater therapeutic benefits as postural and firing-order evaluations are incorporated into their pain-management protocol.

Class II: Bowed-Neck Posture

The Class II forward head in Figure 5 (below) represents a good example of synergistic dominance. Note how the reciprocally weakened longus capitis muscles allow the sternocleidomastoids to cock the head and bow the neck. As the tight short cervical extensors (semispinalis, splenius and longissimus) overpower longus colli, the anterior longitudinal ligament reluctantly overstretches, permitting increased neck bowing (Figure 6) (below).

Due to firm attachments at the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments have been assigned the arduous task of stabilizing vital structures, such as the spinal cord and nerve roots. Sadly, the cervical spine’s anterior longitudinal ligament is a much thinner and weaker structure than the posterior. The opposite arrangement exists in the lumbar spine.

Mother Nature’s choice of ligament placement warrants a well-deserved reversal! Due to ligamentous size and strength, these poorly designated structures do not provide optimal neck or low-back support in human upright posture. It is easy to visualize how additional cervical-anterior longitudinal-ligament thickness would help reinforce Class II extensor-dominant bowed-necks. Excessive curve at C4-5 and C5-6 from anterior and posterior ligament laxity is a major cause of cervical disc radiculopathy, facet dysfunction and bone spurring.

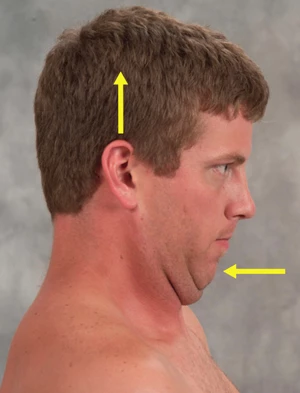

Figure 3 (left): Chin-tucking exercise. Client is instructed to tuck his chin while attempting to rid his head toward the ceiling in a count of three, and then relax. Repeat this maneuver 10 times, twice a day to strengthen longus capitis/coli.

Class II: Bowed-Neck Posture

In Part I, jaw retrusion was shown to be tied to forward-head posture. It was noted how hypertonic hyoids and digastric muscles can create a strong inferoposterior pull, which holds the jaw back as the head moves forward (Figure 7). To keep the mouth from hanging open, the temporalis and masseter muscles are forced into co-contraction. The combined forces of these four muscle groups jam the mandibular condyles and disc into the fossa, causing compression, jaw retrusion, disc displacement and TMJ pain.

By systematically releasing hypertonic hyoid, digastric, masseter, and temporalis muscles, the condyles move more freely in the mandibular fossa as compressional and torsional forces release their grip on temporomandibular structures. Since many aberrant postural patterns begin from the top down, it is sometimes necessary to begin neck sessions with temporomandibular work. Restoring proper jaw alignment often sympathetically balances distorted occipital joint tissues. A unilaterally compressed mandible can sidebend the occiput on atlas, creating compensatory cervical-scoliotic patterns that travel through the trunk and into the pelvis, causing sacroiliac pain and dysfunction.

Figure 4 (left): Head raise test. The supine client raises his head from the table while the therapist closely observes the direction of chin movement. The optimal firing order pattern during the head flexion test is longs captious, longus colli, anterior scalene and SCMs.

Correcting the client’s bite through precise temporomandibular joint and atlanto-occipital work often serves to shut down hyperexcited neural activity (tonic neck reflexes) before compensatory patterns descend to cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar and lumbosacral crossover junctions. Client-retraining exercises that tone weak longus capitis/colli, lower-shoulder stabilizers, posterior rotator cuff, and transversus abdominis musculature provide needed upper-quadrant support for proper head-on-neck balance.

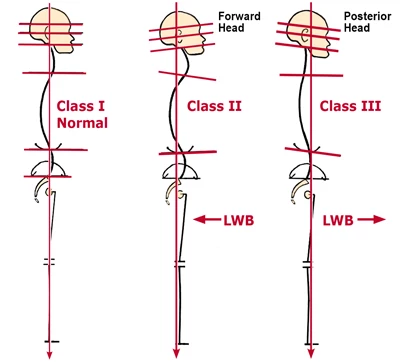

Class III: The Military Neck

In myoskeletal terminology, a Class III protrusive jaw correlates with a flexor-dominant “military neck” due to the strong influence of the deep neck flexors in flattening (and sometimes reversing) cervical lordosis. Figure 5 depicts how a flexor-dominant neck promotes jaw protrusion or vice versa. Class III distorted postures are commonly seen in clients presenting with an abnormal jaw overbite. The resulting posterior head shift and compensatory cervical, thoracic and lumbar adaptations force the body to fall behind the line of weight bearing (LWB).

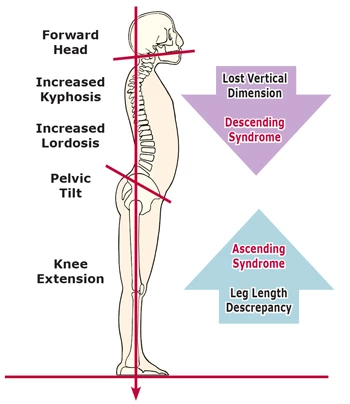

Figure 5: The three most common neck and jaw postural patterns. When comparing Class II and III structures to class I, normal, the line of weight hearing (LWB) falls more posterior to the plumb line in the Class II, retrusive jaw. (exterior-dominant neck) and anterior in the Class III, protrusive jaw (flexor-dominance neck). Class II presents with hyperlordotic neck with the apex peaking at about C4-5, C5-6… the two most common areas of disc herniation in the cervical spine The Class II subject is also likely to experience TMJ dysfunction as the mandible is crammed into the condyles.

Figure 6: Anterior longitudinal ligament. The cervical spine’s ligament is a much thinner and weaker structure than the posterior. When reciprocally weakened, longus capitis muscles allow the SCMS to cock the head and bow the neck, the anterior longitudinal ligament overstretched creating an unstable cervical spine.

From a sagittal view, these structural compensations manifest as knee hyperextension, reduced lumbar lordosis, decreased thoracic kyphosis, and occipitoatlantal flexion. There is no mistaking this type of straight neck. As the jaw protrudes and head cocks forward, normal cervical lordosis gives way to a vertically aligned neck. Fortunately, few clients present with a true Class III block-on-block flat-necked posture but those who do present a major therapeutic challenge. Structural integrators generally agree that it is much easier to remove excessive spinal curve than to create it.

Perhaps the most common traumatically induced instigator of this straight-necked disorder occurs from rear-end acceleration/deceleration whiplash injuries. As the neck and head whip back into hyperextension longus capitis/colli, anterior scalenes and anterior longitudinal ligament can be strained or torn (Figure 6). The healing process is accompanied by a muscle-and-ligament shortening process, as collagen bundles and injured sarcomeres randomly lay down adhesive scar tissue, causing facet compression, disc flattening and loss of cervical curve.

Class IV: The Straight Neck

One final forward-head posture that merits discussion is the capital extensor-dominant neck. This ornery, often misunderstood cervical spine abnormality has risen in popularity primarily due to the proliferation of computers and other work terminals. With every hour spent leaning over a computer, stubborn, posturally induced muscle-imbalance patterns sink their oppressive tentacles into deep spinal structures.

Chiropractors often refer to this Class IV head-forward posture as a “straight neck” (Figure 7). This label has caused much confusion since the neck appears to be flexing forward and in no way resembles the block-on-block military neck described earlier.

Figure 7: Class IV “strait necks.” Forward-drawn straight-necked postures are the most commonly seen of all aberrant upper-quadrant pattern. They are typically accompanied by retrusive jaws, exaggerated lumbar. thoracic curves, and leg length discrepancies. Class IV necks are confusingly labeled as straight due to loss of cervical cure.

During prolonged sitting, the capital extensor-dominant neck begins losing the battle with gravity as deep stretch-weakened extensors allow the neck to forward-bend on the thorax. Close observation of Class IV necks shows the cervical spine forward-bending segment by segment, beginning with: C-7 flexing on its inferior neighbor, T-1; C-6 on 7; 5 on 6; etc. Somewhere between C2-3 and the cervicocranial (atlanto-occipital) junction, the brain begins to apply the brakes by neurologically contracting the suboccipitals and other capital extensors in an effort to pull the head back up on the neck to level the eyes.

Forward-drawn, straight-necked postures are the most commonly seen of all aberrant upper quadrant patterns, and like Class II bowed-necks, are often accompanied by retrusive jaws. However, in Class IV necks eccentrically-contracted cervical extensors such as semispinalis, splenius and longissimus cervicis are weak and overstretched, allowing the neck to move forward on the thorax; there is no bowing. Conversely, all the capital extensors (attaching to the occipital ridge) are stuck short in sustained isometric contraction. Fortunately, the concentrically contracted capital extensors (semispinalis capitis, splenius capitis, longissimus capitis, suboccipitals and upper trapezius) are easy to lengthen using specific deep-tissue and assisted stretching routines, such as those demonstrated in Figures 8 and 9.

Figure 8: Extensor release. The therapist’s left hand braces the anterior surface of the client’s left shoulder, while the right hand reaches under the occipital ridge, hooks the fascia with soft finger pads, and right-rotates the client’s head. The client inhales to a count of five while gently left-rotating head against the therapist’s resistance. Upon exhalation the therapist produces a counterforce between his two hands by depressing the client’s left shoulder while slowly sweeping along the occipital ridge to release tight capital extensors.

Everything’s Connected

Such compensatory activity leads to increased muscle tone, scoliotic patterns and joint dysfunction at critical cervicocranial, cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar and lumbosacral transitional zones. In the presence of pelvic obliquity and resulting spinal soft-tissue compensations, treating the neck in isolation offers purely a temporary and limited effect. Regardless of the type of pain the client is experiencing, posture should be persistently targeted. Some mistakenly believe pain-management postural integration to be overly complex and too time-consuming. However, technological advances detailing predictable muscle imbalance patterns (possibly ingrained from third-trimester trimester fetal positioning) have simplified and elevated the manual therapist’s ability to assess and correct distorted postural patterns.

It is tempting for therapists to immediately resort to chasing the pain rather than developing sensible strategies to effectively deal with the client’s problem. Both client and therapist often settle for any immediate symptom alleviation. Yet a strongly holistic approach that focuses on bringing the body back into balance offers more satisfying long-term outcomes that ultimately help prevent future recurrences of acute pain and leads to more productive living.

Figure 9: Semispinalis capitis release. The therapist’s right hand contacts the client’s left shoulder by sliding his arm under the client’s neck. As the client’s head is lifted, the therapist’s left arm slides under and rests on the client’s right shoulder. By slowly depressing both shoulders, the head is raised to the first pain-free flexion barrier. The client inhales while gently extending the head against the therapist’s resistance for the count of five, and relaxes. As the therapist extends arm and depressed shoulders, semispinalis capitits muscles are post-isometrically lengthen. Repeat three times. Discontinue if radiating pain is experienced during head and neck flexion.

Reprinted with permission from Erik Dalton.com

Erik Dalton, Ph.D., is executive director of the Freedom From Pain Institute, creator of Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques, and author of three best-selling manual therapy textbooks and online home-study programs. Educated in massage, osteopathy, and Rolfing, he resides in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and San Jose, Costa Rica. View his articles and videos at www.erikdalton.com or Facebook’s Erik Dalton Techniques Group.

Erik Dalton, Ph.D., is executive director of the Freedom From Pain Institute, creator of Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques, and author of three best-selling manual therapy textbooks and online home-study programs. Educated in massage, osteopathy, and Rolfing, he resides in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and San Jose, Costa Rica. View his articles and videos at www.erikdalton.com or Facebook’s Erik Dalton Techniques Group.