Biotensegrity: Structural Stability and Ease

“Feeling held versus holding the body upright” is how I would describe a felt sense of tensional integrity. Where standing or walking feels effortless. There is little or no strain, and there is no need to engage the core, align the spine, or activate individual muscles. A sense of wholeness or oneness arises when there is no strain. As your shape shifts from within, the tissue “phase changes” from stiff to soft. “Plumping, juicing, and hydrating” to enhance the way the body distributes force. As fascia “comes home,” you may notice a spontaneous sigh—a sense of space, not only in your body but your whole life. From this calm and quiet, your body might even start to sway or spiral. It is Stephen Levin’s principle of biotensegrity that guides this sensory awareness.

We have imagined our body as a two-dimensional mechanical system of levers activated by individual muscles. We need muscle strength, effort, and resistance to withstand the force of gravity.

Tuning into our sensory wisdom to explore the principles of biotensegrity connects us to an embodied awareness of the nature of our design. It helps you notice what “feels right.”

What is Biotensegrity?

Let’s start with tensegrity, a word invented by the architect Buckminster Fuller to mean “tensional integrity.” It describes three-dimensional structures, struts, and cables held by the opposing forces of continuous tension of the cables and discontinuous compression of struts. Artist Kenneth Snelson, a student of Fuller, called it “floating compression.” This means that the struts do not touch each other. They look as if they are floating in the air. This equilibrium makes the structure stable, energy efficient, and better at absorbing shock than a compression structure.

Let’s start with tensegrity, a word invented by the architect Buckminster Fuller to mean “tensional integrity.” It describes three-dimensional structures, struts, and cables held by the opposing forces of continuous tension of the cables and discontinuous compression of struts. Artist Kenneth Snelson, a student of Fuller, called it “floating compression.” This means that the struts do not touch each other. They look as if they are floating in the air. This equilibrium makes the structure stable, energy efficient, and better at absorbing shock than a compression structure.

In the ’70s, unsatisfied with the explanation of spine mechanics, orthopaedic surgeon Stephen Levin began searching for a structural model of the spine that resonated with him. Seeing a model of a dinosaur at a museum, he wondered about the mechanics of holding the neck of this specimen in suspension. He saw the answer in a sculpture called “The Needle Tower,” a tensegrity structure built by Kenneth Snelson. Levin described seeing “pipes floating up in space, not touching each other. Just hanging, suspended in the air.”

Levin’s aha moment led to biotensegrity, the term he introduced to apply the principles of tensegrity to biology. That nature has an algorithm, a code for the structure of living organisms. You may know this code as sacred geometry, fractal geometry or Fibonacci spirals.

Structural geometry in a kiwi fruit.

Tensegrity Theory

“Erector spinae” means holding the spine upright. This is not so, according to Levin.

In his lecture “Tensegrity Theory,” Levin shares how.

- The curved neck of the ostrich has hardly any posterior muscles holding it up.

- The vertebrae are suspended in the tensional network. Just like the struts in Snelson’s tower, none of the bones in the body touch each other. Nor do the struts pass through the center of the structure. A non-linearity that gives tensegrity structures stability with minimum use of energy.

- Shear force is a term used in two-dimensional anatomy to describe how a vertebra slides forward or backward on the vertebrae below due to the force of gravity or adding a load, as in a herniated disc. That does not apply in tensegrity geometry, and is not what happens in the body. Force is omnidirectional, distributed throughout. The spine does not compress when we bend forward. Strain has to do with electromagnetic frequency and not load.

- The triangle is the most stable structure in geometry. Tensor structures get their stability from three-dimensional triangulated geometry. The icosahedron, a 20-faced triangulated sphere, is the architecture of all living systems.

- From the opposing attract/repel forces of a single cell to the whole organism, it is a self-organizing arrangement of icosahedrons.

- Biotensegrity structures are shaped by electromechanical energy, a sensory system independent of the nervous system. Strain, pain adhesions, and stuckness are shaped by frequency. Change the frequency and the structure shape changes.

Biotensegrity and Effortless Motion

Tensegrity chain – Graham Scarr (with permission to Yasmin Lambat)

In his book Biotensegrity, The Structural Basis of Life, osteopath Graham Scarr describes geometry in motion as:

- Closed kinematic chain: A linked geometrical mechanism that moves the whole body with extraordinarily little effort. Initiate movement in one part, and the whole body will move.

- Non-linearity: In linear biomechanics, the mechanical stress is equal to strain. Not so in biotensegrity. The force is omnidirectional. We can take greater stress before the structure strains because of the principle of “non-linearity.”

- The structure is auxetic: Auxetic materials get thicker, expanding in every direction when pulled. Unlike elastic, which gets thinner in the middle, this auxetic property optimizes our shock-absorbing, energy-storing capacity.

- Chirality: Chilrality describes how these geometrical chains intertwine. Collagen fibers and DNA are like the strands of a rope woven in chirality, one way then the other. When you open a jam jar, notice how your hand moves one way and the bottle the other.

- We are spring-loaded. The spiral nature of chirality allows us to store energy like a spring, making movement happen with minimum energy. Strength comes from the efficiency of a spring-loaded system, not muscle mass.

Pain, Strain, Fatigue and Stuckness

You’ve been hearing how super-efficient, stable, and energy-efficient we are up until now. So, what happens when we feel pain, strain, or fatigue?

Fascia is the soft tissue matter, the liquid crystal, which becomes the struts and cables of our geometry. It has an electromagnetic property that makes it sensory. It vibrates, oscillates, and resonates. (John Sharkey – site-specific tuning pegs 2020).

- Fascia under strain, pain, or restriction is a sign that we are out of tune. We often describe “feeling out of tune.”

- Approaching pain, strain, posture, and restriction from changing the frequency can help restore homeostasis.

- A light touch, gentle motion, or frequency-specific microcurrent therapy (The Resonance Effect, Carolyn Mcmakin) can change the phase and resonance of fascia, easing strain and pain without the need for deep tissue massage, foam rollers, or fascia blasters.

3 Ways to Explore and Apply Biotensegrity

Here are three somatic explorations that help us apply the core principles of biotensegrity:

1. Standing with No Effort

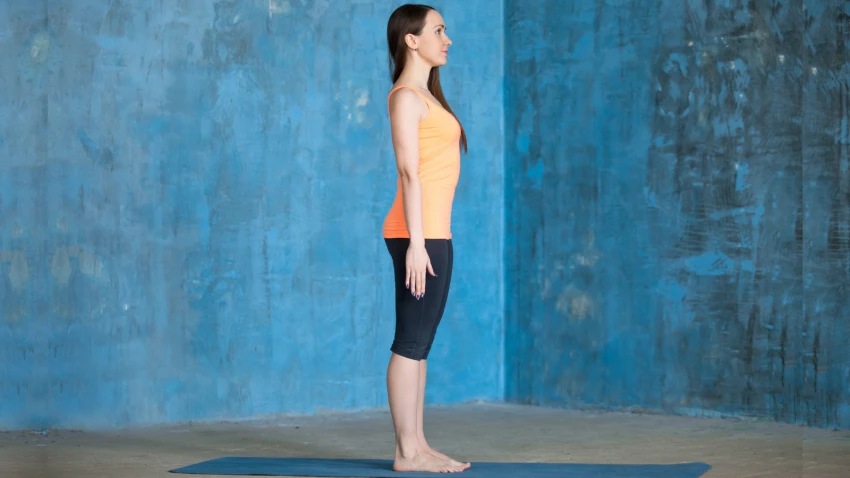

In this practice, we explore the principle of omnidirectional force distribution, comparing how we were taught to stand to how we can allow our body to self-organize through fascia sensing.

How We Were Taught to Stand in Alignment:

- Stand with your feet hip-distance apart. Knees, ankles, and hips are stacked in alignment.

- Create space between the vertebrae of your spine from the base to the crown of the head.

- Stand tall, chin gently tucked to lengthen through the back of the neck.

- Shoulders glide away from your ears.

- Widen across the collarbone.

- Glide the tailbone down and draw your pelvic floor up to engage the core.

How to Self-Adjust in Standing

Can you arrive in a standing position in whatever way that happens for you?

- Can you take a moment to pause, close your eyes and tune in to your body, noticing whether the way that you’re standing feels comfortable for you?

- If not, where do you notice areas of strain or discomfort? How can you adjust yourself to soften areas of strain from within? To find what feels good.

- What may help is to imagine your body as a container of gel. How soft is that gel? Could you adjust to soften any areas where the gel feels stiff and under strain? Create a sense of space.

- What happens when you soften the area around your mid-spine? Around your heart, your throat, your lower back. Do you feel more rested?

- You may notice that your body begins to sway, or maybe not if there is strain.

- A spontaneous sigh may arise when you ease the strain.

Tuning into the interoceptive nature of fascia (how stiff, strained, or soft fascia feels) helps us discover which version of standing is more energy efficient.

2. Stability Without Needing to Engage the Core

Firstly, the core is not separate. Fascia is continuous from the inside out. There are no layers. (John Sharkey, Anatomy for the 21st Century, 2018). We may experience a “phase change,” a sensation that goes from soft to stiff or stiff to soft. When you actively engage “your core,” you are adding strain to a pre-tensioned structure. Here is one of my favorite ways to help you notice that the core is not separate. What happens when you engage what you imagine to be your core? You need a partner for this.

- Get your partner to engage their core in an upright stacked posture, co-contracting the muscles of the trunk, as you may have been taught. Stand to their side as if standing beside a bowling pin. Give them a little push from the side, the back, and the front, and notice what happens.

- Now, ask them to stand at rest. Push again with less strain and in the most comfortable way, and notice what happens.

Swap with your partner and notice the sensation in your own body. A rigid structure is less stable than a structure that can distribute force throughout.

Here is an everyday motion that demonstrates stability in motion. When you reach for something on a top shelf, notice whether your body takes a spontaneous breath in. The whole body expands and then returns. That motion is like the folds of an accordion. Your body self-stabilizes ON AN IN-BREATH!

3. Soft Body Bounce

Fascial integrity relies on frequency for suppleness and elasticity. Shape-changing intuitive whole-body movements replace stretching to nourish and revitalize the fascial matrix. Fascial unwinding, pandiculation, and micromovements like coaxing, bouncing, and pulsing emerge spontaneously.

- Begin in a standing position in the most comfortable way for you.

- Can you explore a wider stance and notice if that brings some relief to areas of strain?

- If your body were a gel container, how stiff or stuck is the gel?

- Can you soften the gel and find a way to rest in your body with the least amount of strain?

- Could you add a little bounce with your knees, as if the knees have springs?

- Notice how the rest of the body responds.

- How can you use this quiet, bouncing motion to nurture and nourish any areas of strain or stuckness?

I hope your sensory wisdom has helped you reconnect with your true nature.

Also, read...

Age-Related Posture Slump? Yoga Can Help Alleviate Hyperkyphosis, Study Suggests

Free Yoga Video: 3 Somatic Yoga Practices to Help Enhance Postural Awareness

How Well Are You Aging? An Easy Test of Health and Longevity

Related courses

Breath as Medicine: Yogic Breathing for Vital Aging

Yoga and Myofascial Release: Releasing Chronic Tension with the Bodymind Ballwork Method

Yoga and Detoxification: Tips for Stimulating Lymphatic Health

Meet Yasmin Lambat, Master Somatic Movement Therapist, Educator, and Founder of SomaSensing Body Unwinding. A trauma healing somatic movement practice based on the emerging research on fascia, biotensegrity, and nervous system regulation.

Her movement and manual therapy experience spans 30 years. It includes training as a Yoga and Polestar Pilates teacher as well as a myofascial release therapist. It was her introduction to somatic movement that paved the way to somatic healing.

In her workshops and coaching services, Yasmin draws on the latest research and best practices in the field to provide a practical embodied experience for integrating somatic movement therapy and somatic practices into participants’ lives.