Fascia and the Vagus Nerve: Healing from the Inside Out

Article At A Glance

Have you ever had a morning in which you woke up with a painful knot in your neck? What happened? Did you sleep in a funny position or was it the wild dream that had you tossing and turning? Maybe it was due to the stressful work meeting you had the day before or because you feel worried about something in the future. While this may sound strange, your tight neck could even be related to what you ate the night before or an event that happened many years ago.

Intuitively, we all know that stress shows up in our bodies as muscular tension. But, when we look more closely at the body-mind connection we recognize that fascia plays a key role in how we physically experience stress and heal from traumatic events. Furthermore, since the vagus nerve plays an important role in communicating changes in fascia to your brain, we explore how attending to vagal tone helps you to heal.

Fascia also plays a key role in your resilience. You can nourish the fascia and the vagus nerve by attending to your body and mind through sensory awareness, conscious breathing, and mindful movement. These tools help you to recover more quickly from stressful experiences and heal traumatic events from your past.

Understanding Fascia

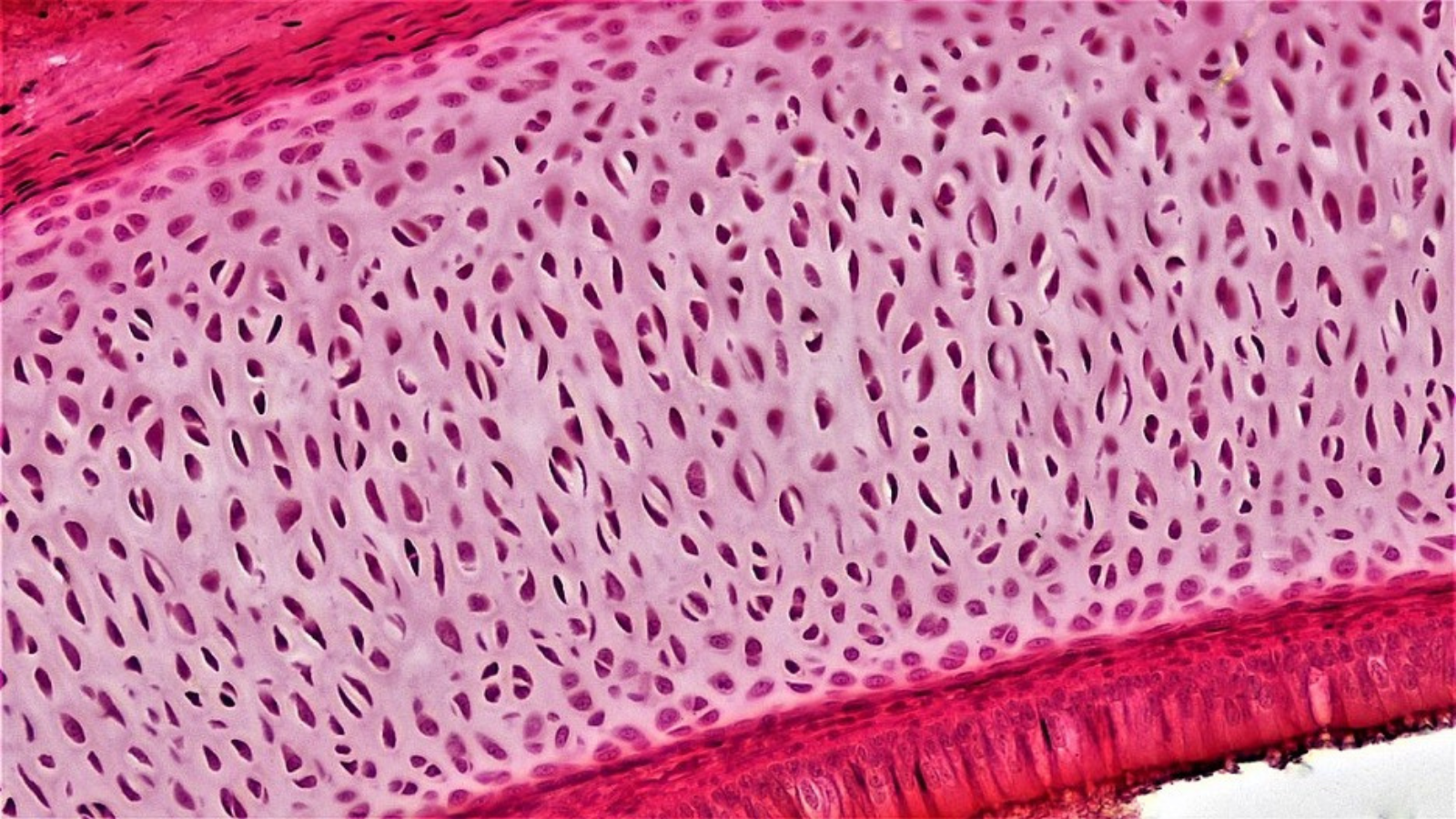

Fascia, also known as connective tissue, is a fibrous web that extends into every structure and system of your body. There are many different types of fascia (see the images in this post to get a feeling for the varieties). These include superficial layers just under your skin and deeper layers that wrap around your bones and muscles. Fascia provides a nourishing and lubricating layer around your lungs which intertwines with your pericardium—the layer of fascia around your heart. You’ll also find connective tissue around all of your digestive organs. One of the key functions of a healthy fascia is that it allows the surrounding tissues to slide and glide across each other.

Fascia is also found in each of your endocrine glands, so much so that the founder of Integral Anatomy, Dr. Gil Hedley, refers to fascia as a whole-body endocrine organ. For example, fascia plays a key role in transmitting hormones (e.g. adrenaline, estrogen, insulin, thyroid hormones, oxytocin) and neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin, dopamine, GABA, acetylcholine) throughout your body. Thus we see that fascia is also deeply intertwined with the nervous system. Furthermore, fascia plays a key role in the immune system.

Lack of movement, emotional stress, physical injury, and historical trauma can lead to the stickiness or hardening of fascia. There is a small amount of this hardening of the fascia that occurs each night when we sleep. Dr. Hedley refers to this as the “fuzz” that accumulates between the layers of the fascia. Over time, this fuzz can build up and is associated with vicious cycles of chronic pain, systemic inflammation, histamine intolerance, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome (myalgic encephalomyelitis). The good news is that mindful movement, deep breathing, and massage all help to melt the fuzz and rehydrate your fascia. (Scroll down to the bottom of this post for a video practice).

Fascia and the Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve plays a key role in communicating changes in the fascia to your brain. You can think of the vagus nerve as a bi-directional information highway between brain and body that helps regulate your autonomic nervous system. Stressful events engage your sympathetic nervous system through the fight-or-flight response. The sympathetic nervous system is like a gas pedal that speeds you up. The vagus nerve provides a “vagal brake” which slows you down. When fully engaged, the vagus nerve allows you to let go of fight or flight for the purpose of resting, digesting, and bonding with others during times of safety. However, in situations that are traumatic or life-threatening, this vagal brake can kick in an abrupt manner bringing you to a hard stop. This is referred to as vasovagal syncope which can lead to nausea, dizziness, or fainting.

The vagus nerve also plays a key role in your digestive system health as it innervates (extends into) the stomach, spleen, liver, intestines, and colon as part of the gut-brain axis. The gut has been called our second or “enteric” brain, in part because the gut is capable of producing the same neurotransmitters found in the brain. These neurochemicals are communicated between our digestive system and brainstem via the vagus nerve. However, the fascia plays a key role in the quality of the conversation.

You can think of fascia as the largest sensory organ in your body as it houses 250 million nerve endings. What is fascinating is that there are three times as many sensory neurons as motor neurons. Thus, fascia has a primary role in communicating information about what’s happening in your body to your brain. The tissues of the fascia are meant to expand and contract.

Fascia’s Role in Trauma Response

However, when we have experienced a physical injury or emotional trauma we tend to go into shock, which restricts movement to ensure our survival. Simply put, we either move into freeze (tonic immobility) or faint (collapsed immobility) responses. If this trauma response doesn’t resolve, we can feel stuck in having too much tone in the body or too little. We lose that capacity to rhythmically expand and contract.

Unresolved trauma has consequences on our emotional and physical health. Not only can the fascial fuzz build-up, but without movement, we tend to lose our connection to our bodily sensations. We are more likely to feel disconnected or even dissociated. So, physical and emotional healing involves restoring a relationship with your body. However, when you have chronic pain or illness it is often difficult to reconnect to the body.

You may feel as though your body has betrayed you or that your illness has been a source of trauma in and of itself. Or, reconnecting to sensations might feel frightening because you are more likely to experience painful emotions or traumatic memories. So, the key is to progress slowly on the path toward embodiment. Fascia and the vagus nerve hold the keys to how to do this safely.

Neuroception

Dr.Stephen Porges, the developer of the polyvagal theory, coined the term neuroception to reflect the process by which the autonomic nervous system scans for and responds to internal and external cues of threat. This happens automatically (without conscious awareness), which leads to chronic hypervigilance or high sensitivity to stress. However, you can also engage in conscious neuroception by observing your body for signals that give you feedback about the state of your nervous system. By observing your body, you can determine if you are feeling calm and connected, keyed up in “fight or flight,” feeling frozen, or feeling shut down and collapsed.

How to Know if Your Body is in Stress Mode

Here are some of the signals that your body is under stress:

- digestive distress (bloating, acid reflux, IBS)

- increased muscular tension (especially in your diaphragm, ribcage, chest, or psoas)

- loss of postural tone or feeling collapsed

- changes in how you are breathing (fast, shallow, held)

- feeling jumpy, restless, fidgety

- excessive still or feeling “frozen”

Self-knowledge of your body and mind allows you to engage in strategies that bring you into an optimal zone of nervous system regulation. For example, if you feel dull, numb, or collapsed you may need to upregulate your nervous system. You can do so with movement and breath practices that engage mobilization strategies to unwind from chronic freeze-or-faint responses. You can also explore how it feels to tune into cues of safety that allow you to rest into stillness and initiate a “relaxation response.” Be patient. Reclaiming healthy stillness often takes longer to develop.

How to Know if Your Body is in the Optimal Zone

How do you know that you are in the optimal zone of nervous system regulation? I offer the following “8 Cs” as cues that you’re in the zone.

You know you are in the zone when you feel:

- Calm in your body and mind

- Connected to yourself and others

- an enhanced sense of Clarity

- Compassionate toward yourself and others

- Creative and playful

- Courageous and empowered

- Curious about your inner experience and needs

- Confident that you can take action in a meaningful manner

Embodiment, Fascia, and the Vagus Nerve

Embodiment is the conscious awareness of your felt sense of self. You can wake up the connections between fascia and your vagus nerve when you breathe deeply or stretch your body. This helps you to become aware of your sensations, and you will begin to notice changes that occur in your muscles, organs, or heart rate. It is through awareness of interceptive changes that we wake up our internal sense of self.

So, if you woke up with a sore neck, you can explore your sensations to gain insight into why you feel this way. For example, you might begin to notice that the tight feeling in your neck corresponds to a feeling of tightness in your throat, tension in your chest, or tightness in your belly. Or, you might begin to sense emotions of sadness, anger, or fear.

Physical tension in your muscles and connective tissue is a protective layer that we call “armoring” in somatic psychology. It is held as a form of memory and will not release until you know that you are safe. That is why we cannot force change upon ourselves. Doing so may cause a “rubber band” effect in which you stretch too far, which leads to further contraction.

Talk—and Listen—to Your Body

Therefore, I invite you to think of an embodiment practice as a conversation with your body. You listen to sensations and respond with movement. Then, ask your body, “Did I get it right?” Listen for feedback in the form of sensation. Moving and breathing should feel good enough and while you may feel an “edge” of discomfort you are still in your optimal zone of nervous system regulation.

Notice if you have a tendency to be aggressive with yourself. If you experience a “stuck” sensation, gently rest your attention there. Ask this part of your body what it needs from you. See if you can soften and respond with your 8 Cs. How might curiosity help? Can you engage in self-compassion? Perhaps creative and playful movements such as gentle rocking or humming create a greater sense of calm or connection with yourself.

A Practice for Fascia and the Vagus Nerve

If you’d like, try this short practice for the fascia and the vagus nerve. This practice invites you to explore a relationship with your body through sensing, moving, breathing, and rolling to release tension in your diaphragm, chest, ribcage, and sacrum. Releasing tension from these areas not only helps with digestion but awakens your sensory-motor system, which invites greater brainstem regulatory integrity.

As with all practices, we tend to benefit from repeating them on a regular basis. Over time, you can build a reservoir of somatic intelligence that fosters an increased connection to yourself.

Also, read...

Free Yoga Video: Breathing for Pelvic Floor Health: Two Practices to Deepen Your Breath

How Healthy Is Your Nervous System: Polyvagal Theory Made Simple

Related courses

Breath as Medicine: Yogic Breathing for Vital Aging

Yoga and Myofascial Release: Releasing Chronic Tension with the Bodymind Ballwork Method

Dr. Arielle Schwartz is a licensed clinical psychologist, wife, and mother in Boulder, CO. She offers trainings for therapists, maintains a private practice, and has passions for the outdoors, yoga, and writing. She is also the developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy which applies research on trauma recovery to form a strength-based, trauma treatment model that includes Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), somatic (body-centered) psychology, mindfulness-based therapies, and time-tested relational psychotherapy.

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control and Becoming Whole (Althea Press, 2016)

- EMDR Therapy and Somatic Psychology: Interventions to Enhance Embodiment in Trauma Treatment (Norton, 2018).

- The Post-Traumatic Growth Guidebook: Practical Mind-Body Tools to Heal Trauma, Foster Resilience, and Awaken your Potential (Pesi Publications, 2020)

- A Practical Guide to Complex PTSD: Compassionate Strategies for Childhood Trauma (Rockridge Press, 2020)