Anatomy Trains, Yoga and the Power of Connections: An Interview with Tom Myers

Tom Myers is the author of Anatomy Trains, a book that reimagines our anatomy as an interconnected, holistic system instead of a series of independent parts. In this interview, he discusses how the Anatomy Trains concept can help yoga teachers and practitioners better understand what happens in yoga postures and how to make progress in their practice.

YogaUOnline: Tom, you are famous in bodywork circles for developing the Anatomy Trains concept. This model is often referred to as “the anatomy of connection.” Tell us what this means and how you developed this concept.

Tom Myers: Well, the anatomy that we’ve been working with for the last four hundred years is the anatomy of isolation or the anatomy of parts. When you try to apply that to yoga, it really doesn’t translate very well. For example, when you go into a Downward Dog, it doesn’t make sense to think about whether you are stretching the hamstrings, the plantar flexors, or the fascia that goes over the sacrum because you’re stretching all three. And significantly, how deeply you go into that pose and where the pose fails or could be improved depends not just on this structure or that structure, but the relationship among the structures.

So it’s not that Anatomy Trains is that new or that different. But it applies so much more easily to yoga, where you are putting a stretch, a stress, or a strain into large sections of the body at once.

YogaUOnline: How did you come up with this concept?

Tom Myers: I was trying to teach anatomy to students at the Rolfing school. We started making a game, because there was nothing connected about any of the anatomy books then. So I started making a game of saying, “Well, can you go from this muscle to this muscle in a straight line? And then can you go from this muscle to this muscle in a straight line.” And I called it the Anatomy Trains because it literally was a game for my students. But then, I became more serious about it and turned it into a system.

YogaUOnline: Very interesting. In terms of understanding how this relates to movement in the body, give us an example. You referred to the spiral lines. And, of course, the equivalent movement in yoga anatomy, or rather yoga functional anatomy, would be rotation/twisting postures.

Tom Myers: Exactly.

YogaUOnline: So, if a person is having limitations in range of motion, in twisting postures, in tradition Western anatomy, we would look at some of the muscles involved in, for example, trunk rotation. Tell us how you would be looking at that from the standpoint of Anatomy Trains and what implications that has for our yoga practice.

Tom Myers: Well, it’s beneficial for yoga teachers to know these things because they’ll be able to see more of what’s going on as their students go through different postures. If you watch someone doing the Triangle Pose, for example —which puts one upper spiral line into a twist and requires the engagement of all the muscles along the other spiral line—there could be a fault in the ability of the muscle or a fascial fabric to elongate enough to get into the pose. Or there might be a lack of strength in an opposing muscle that couldn’t support the ribcage or the neck so that the spiral is clean, so to speak….

Yoga teachers need to be able to see when their students are doing it differently on one side and the other and then take steps to either strengthen or lengthen, depending on what’s needed.

But the brain needs to have that concept in mind to be able to see these things. So practice, practice, practice. Just keep looking for what’s not lengthening as you watch your students. Knowing the Anatomy Trains lines, knowing what anatomy is involved in each of the myofascial meridians, is very helpful in being able to see what is going on in a pose. Once you know what’s going on, you can cue students so that the pose becomes more even.

What we’re looking for in the Anatomy Trains vision is an even tone across the whole line and even tone along the lines and a good relationship among the lines. Injury occurs where there’s no give. And so, the idea of yoga, and the idea of the kind of bodywork that I do, is to even out the tone and make it possible for that little bit of give to happen, no matter what functional movement you’re doing. However, we use yoga poses as models of functional movement to see that.

YogaUOnline: When we think in terms of movement, in traditional anatomy, it is described in terms of ropes and pulleys. But you’re saying movement works in a very different way in the body. Is that correct?

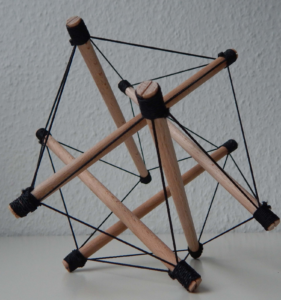

Tom Myers: Yes, that takes us to the concept of tensegrity, which tells us that the bones are not a solid structure on which the muscles hang. Instead, it is much more that the bones float within a balanced tension of the muscles and the fascia. So when you go into yoga poses, when you go into the extreme of a movement and then extend your extreme by stretching, you are increasing the amount of resilience in your tissues so that all the tissues give a little.

muscles hang. Instead, it is much more that the bones float within a balanced tension of the muscles and the fascia. So when you go into yoga poses, when you go into the extreme of a movement and then extend your extreme by stretching, you are increasing the amount of resilience in your tissues so that all the tissues give a little.

But Anatomy Trains is not a theory of movement. Movement is a mystery, how we move is a mystery. Scientists like to tell you that they think they know a lot about it, but I don’t think we really have sorted out how movement works in the body yet. The idea that nerves make muscles move is a basic concept. But there are other feedback loops that we have not really explored yet, scientifically, or that we can’t even really articulate that well at this point.

We are at a breaking point in research. The mechanics that we’ve been happy with for the last 350 years are going to give way to a new kind of biomechanics based on more interconnected concepts, like the Anatomy Trains and the idea of tensegrity. I predict that we will begin to look at the nervous system more as a kind of cloud computing than the kind of computing we’ve been doing until now.

YogaUOnline: Yoga postures are unique in that they generally involve movement of the spine, which we don’t get that much of otherwise. I’ve often wondered if this kind of movement creates a stimulation of the nerves that might be, in part, responsible for some of the benefits people are experiencing from yoga practice?

Tom Myers: Well, I’d say it’s more out at the ends of the nerves that the benefit is happening. Yes, there’s some benefit to those nerves sliding through the holes in the spine. But I’d say that the effects come more from the stretching in the limbs or the trunk, wherever the nerves end. Those little nerve endings are listening to the fascia and the muscles, so to speak, and when we stimulate them, it goes right back into the spinal cord and stimulates the part of the brain associated with those nerve endings.

That’s the wonderful thing about yoga. If you allow your practice to deepen, you’ll constantly come across new areas in your body that were forgotten, and you’ll bring them back into your body image or your body awareness.

YogaUOnline: Interesting.

Tom Myers: I would almost say that it is a moral person who makes decisions, feeling their whole body. In the West today, we have so many places in our body that we have forgotten and that we don’t use in our day-to-day lives. So we have to be broader in our movement range, using yoga or some other form of union to feel our body as a complete thing again.

YogaUOnline: Many people believe that intuition is very much tied into feeling that somatic reality, is that your understanding as well?

Tom Myers: Yes, hunches are a physical process. Intuition is a physical process. It’s a process of tuning into your body and thinking of the body as an antenna. I don’t mean to sound New Age-y, but scientifically, your fascia is a liquid crystal. It is arranged in crystalline form. So it could be considered to be a kind of antenna. If you are tuned to it, if you are inhabiting all of it, I think you will make better decisions, than if you are only inhabiting small pieces of it.

That is a part of your mind. Your mind extends all the way down to your feet, all the way down to your hands, all the way into your back. And if you’re only paying attention to your hands and your face and your eyes on the computer screen and you’re otherwise sitting most of the time, you lose access to those kinds of intuitive feelings.