How Can We Stimulate The Vagus Nerve with Our Yoga Practice? Part 1

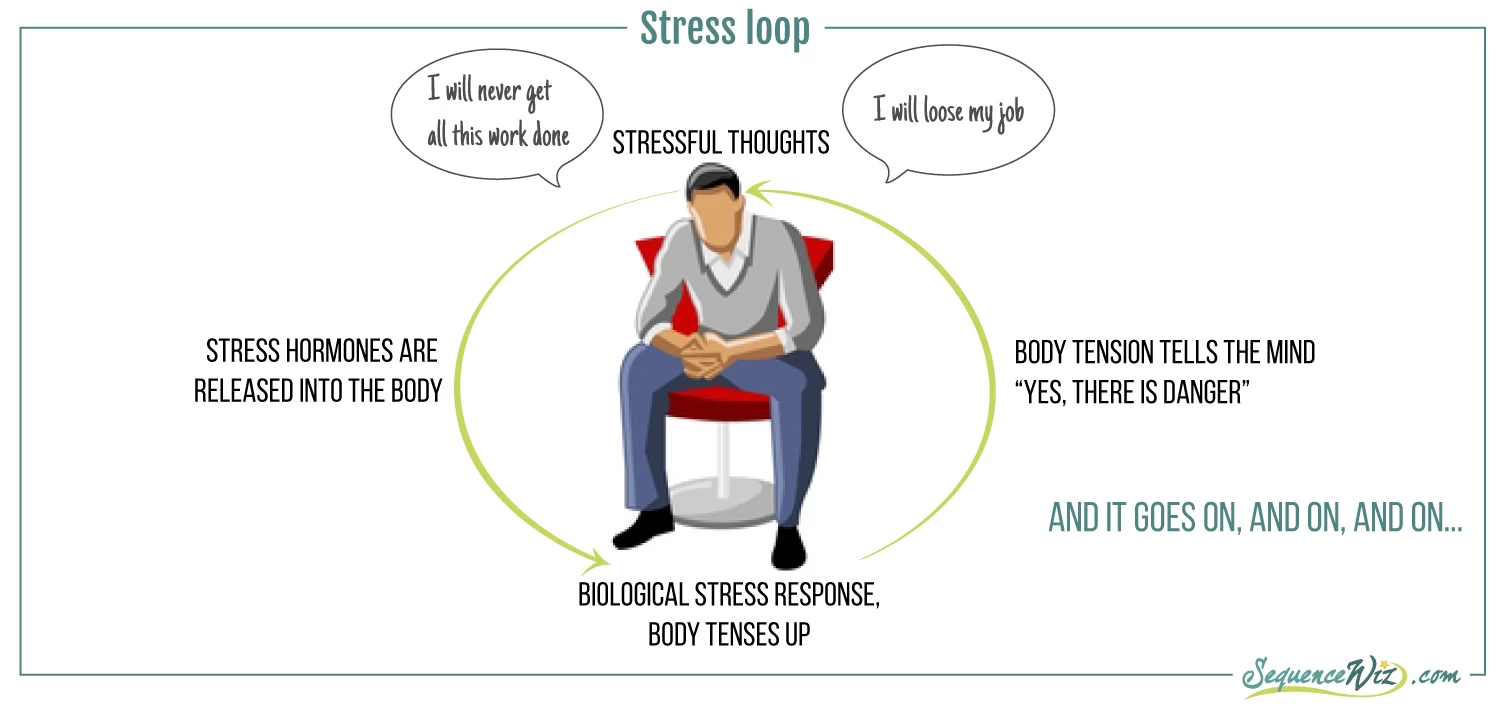

Have you heard the term “stress loop” before? Here is how it works. When your mind perceives something dangerous or stressful it activates the sympathetic nervous system which dumps adrenaline and other stress hormones into your body and your body responds – the blood pulls toward large skeletal muscles, you begin to breathe faster and so on. So your body is now ready to “fight or flight” and sends a signal of readiness to your brain. The brain perceives that your body is wound up and interprets it as confirmation that there is real danger present and continues with the stress response, which, in turn, keeps the body in a fight-or-flight mode, which then sends those stress signals back to the brain – and so the cycle goes on and on.

To break out of the loop you need to activate your parasympathetic nervous system (the rest-and-digest mode) and there are two ways to do it – to convince your mind that there is no more danger or to stop the biological stress response so that the body signals the mind that it is no longer in a fight-or-flight mode. What’s important to us here is that the vagus nerve would communicate both of those messages, since it is responsible for most of parasympathetic messaging both from the brain to the body and from the body to the brain. And since 80% of its fibers communicate the information from the body to the brain, one could argue that the state of the body (whether it’s agitated or calm) has a great impact on the state of the mind.

You cannot directly and consciously stimulate your vagus nerve like you would with an electrical device. But you can indirectly stimulate your vagus nerve by getting yourself into the rest-and-digest mode because this nerve gets activated during the parasympathetic response. How do we do that?

Remember which parts of your body the vagus nerve branches out to? It goes to your throat, lungs, heart and abdominal organs (not the large skeletal muscles). Which of those parts do you have control over? You cannot consciously control your heart, your kidneys or your small intestine, but you can control the depth of your breathing (to a certain degree) and the muscles of your larynx (that open and close the vocal cords and control the pitch of sound), which the branches of the vagus nerve also happen to innervate. So then it would make sense that to facilitate the parasympathetic response in the body (and stimulate the vagus nerve), we would need to exert influence over those two main areas. Let’s focus on the breath first.

It is no surprise that the most commonly suggested technique for parasympathetic activation is deep diaphragmatic breathing. It makes sense – sympathetic response leads to short fast breathing bordering on hyperventilation (because your airways open up wide and you are basically gulping the air in) and parasympathetic activation leads to deep relaxed breathing (since your airways constrict and you will need to take time to breathe in and out to get the same amount of air in). And it works the other way around, too – if you gulp the air in your brain will perceive it as an invitation to fight or flight, and if you seep the air in and let it out slowly your brain will take it as an invitation to rest and digest.

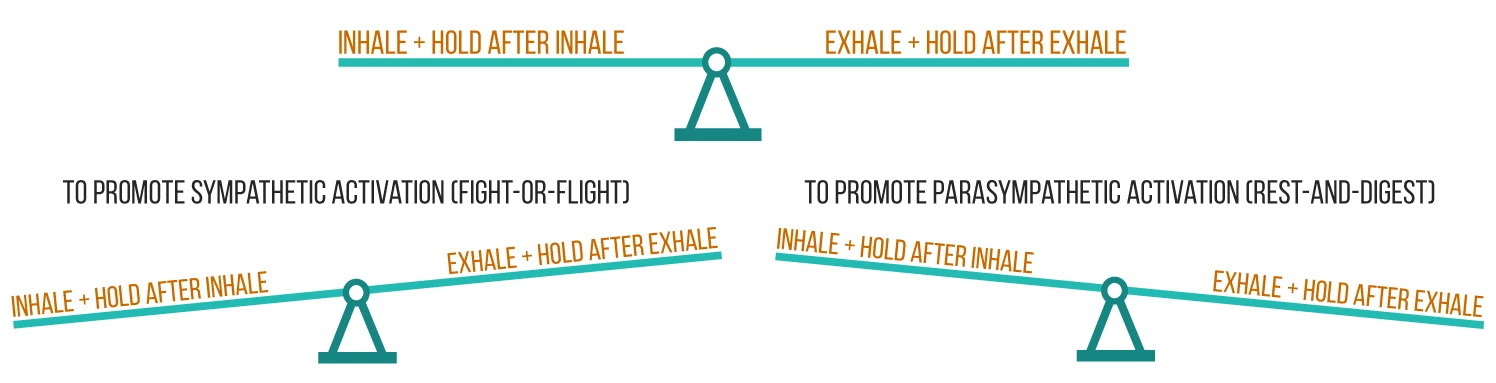

That’s all great; however, not all parts of the breath are created equal. One of my former students who had severe anxiety associated with public speaking said to me once: “I was told that to calm myself down before stepping on the stage I should take a deep breath in, hold the air in for few seconds and then let it out, and do that few times. For some reason it never worked for me.” Here is why it didn’t work for her. Every time you inhale you activate your sympathetic response a bit (and your heart speeds up a little, vagus nerve is suppressed); if you hold the air in, that response is accentuated. Every time you exhale you activate the parasympathetic response (and the heart rate slows down a bit, vagus nerve is active); if you hold the air out for few seconds it will facilitate the parasympathetic activation. So unknowingly my student was revving herself up even more with that breathing pattern instead of calming herself down. That is why the relationship between different parts of the breath matters as much as the depth of the breath.

And this is exactly what the vagal tone is about. It refers to the variability between the heart rate on the inhale and the exhale. The greater that variability is, the higher vagal tone you have, which means that your body can easily switch from the fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest mode and visa versa. It basically reflects your resilience.

“Research shows that a high vagal tone makes your body better at regulating blood glucose levels, reducing the likelihood of diabetes, stroke and cardiovascular disease. Low vagal tone, however, has been associated with chronic inflammation. One of the vagus nerve’s jobs is to reset the immune system and switch off production of proteins that fuel inflammation. Low vagal tone means this regulation is less effective and inflammation can become excessive.”(1)

Apparently, the vagal tone is congenital to some degree (you might be born a “glass-half-full person” indicating a high vagal tone) and to some degree it can be acquired. So technically, the vagal tone is about the relationship between the two parts of the breath (inhale and exhale). How can we affect that relationship so that our bodies become more adept at switching between the sympathetic and parasympathetic modes with greater ease? Well, through the yogic science of ratio, of course! When we work with ratios we work on extending the length of four parts of the breath (inhale-hold after inhale-exhale-hold after exhale) as well as changing their relationship to one another for the purpose of sympathetic/parasympathetic management.

The science of ratio might seem difficult or confusing, but it doesn’t need to be. Think of your breath as a scale with the inhalation part of the breath (inhale + hold after inhale) on one side and exhalation part of the breath (exhale + hold after exhale) on the other side.

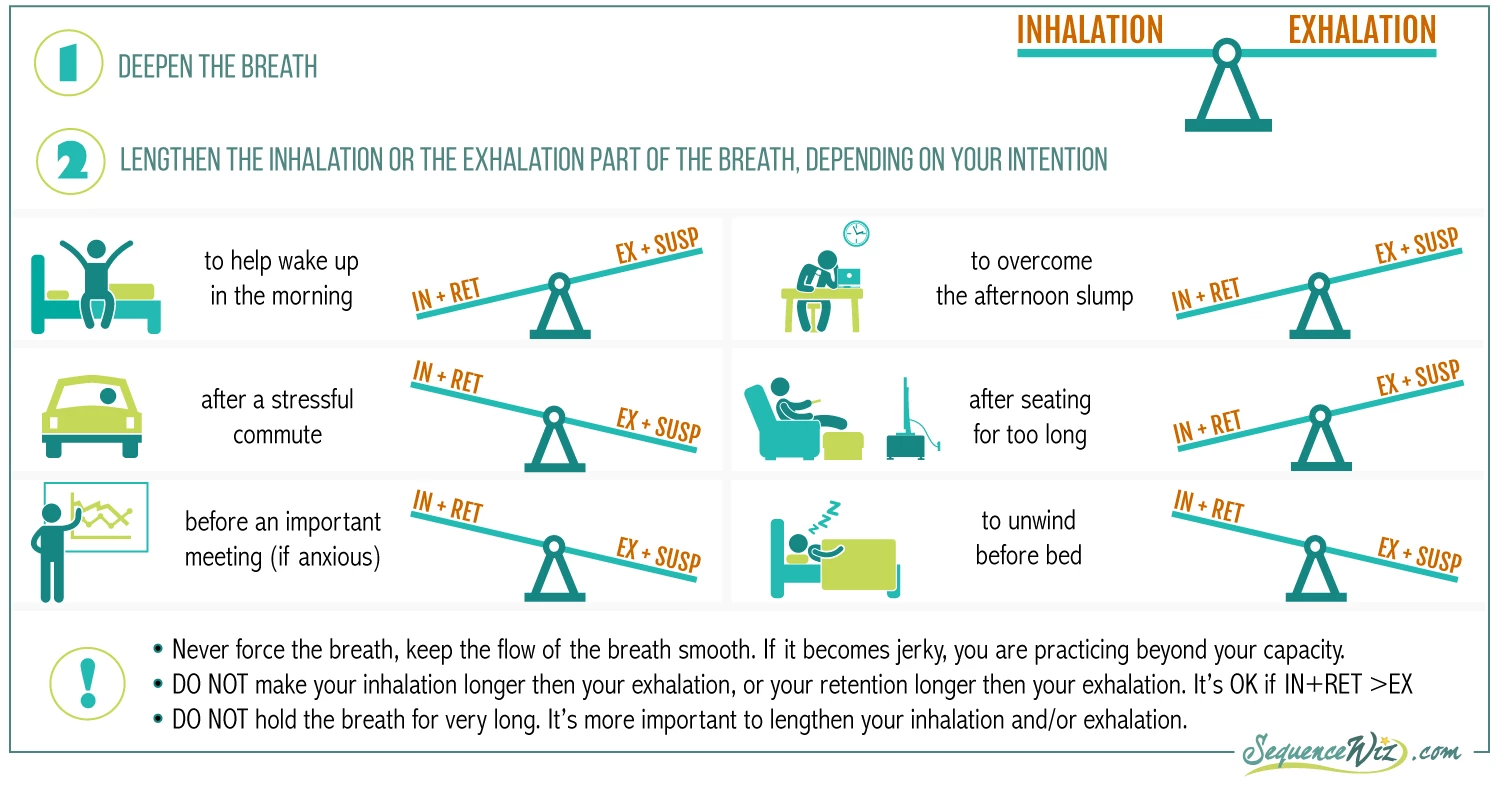

If you want to promote parasympathetic activation and vagus nerve stimulation you would need to gradually lengthen your exhale and pause after exhale. That’s all. The longer you make the exhalation part of the breath in relation to the inhalation part (comfortably), the more pronounced the parasympathetic effect will be. Just keep in mind that deep breathing is still important, so you don’t want to make your inhalation too short – deepening the breath in general is still a priority. Here is quick example of how you can build a simple breath ratio:

Inhale : Hold after Inhale : Exhale : Hold after Exhale

1. 6:0:6:0 – 4 breaths

2. 6:0:8:0 – 4 breaths

3. 6:0:8:2 (adding a pause) – 4 breaths

4. 6:0:8:4 (lengthening the pause) – 6 or more breaths

5. 6:0:8:0 (to transition back to normal breathing) – 4 breaths

This is an example of building a ratio – progressively lengthening the parts of the breath that you are interested in lengthening. If you look at the final ratio (6:0:8:4), you will see that the inhalation part of the breath is 6 seconds (6+0=6) and exhalation part of the breath is 12 seconds (8+4=12) which makes the exhalation part twice as long – this will emphasize the effect even more.

Here are some simple examples of specific application of ratios. Here Retention (RET) refers to hold after inhale and Suspension (SUSP) refers to hold after exhale. (Read an entire article about ratios)

So it appears that ratio work would help stimulate the vagus nerve short-term (during the practice) and increase vagal tone long-term (if you do it consistently). This is very exciting. But, as my teacher likes to say, don’t take my word for it. Try it out and find out for yourself. All you have to loose is stress and chronic inflammation.

Study about this fascinating nerve with YogaUOnline and Marlysa Sullivan: Your Well-being Power Switch- The Role of the Vagus Nerve in Health and Healing

Reprinted with permission from SequenceWiz

Educated as a school teacher, Olga Kabel has been teaching yoga for over 14 years. She completed multiple Yoga Teacher Training Programs, but discovered the strongest connection to the Krishnamacharya/ T.K.V. Desikachar lineage. She had studied with Gary Kraftsow and American Viniyoga Institute (2004-2006) and received her Viniyoga Teacher diploma in July 2006, becoming an AVI-certified Yoga Therapist in April 2011. Olga is a founder and managing director of Sequence Wiz- a web-based yoga sequence builder that assists yoga teachers and yoga therapists in creating and organizing yoga practices. It also features simple, informational articles on how to sequence yoga practices for maximum effectiveness. Olga strongly believes in the healing power of this ancient discipline on every level: physical, psychological, and spiritual. She strives to make yoga practices accessible to students of any age, physical ability and medical history specializing in helping her students relieve muscle aches and pains, manage stress and anxiety, and develop mental focus.

Educated as a school teacher, Olga Kabel has been teaching yoga for over 14 years. She completed multiple Yoga Teacher Training Programs, but discovered the strongest connection to the Krishnamacharya/ T.K.V. Desikachar lineage. She had studied with Gary Kraftsow and American Viniyoga Institute (2004-2006) and received her Viniyoga Teacher diploma in July 2006, becoming an AVI-certified Yoga Therapist in April 2011. Olga is a founder and managing director of Sequence Wiz- a web-based yoga sequence builder that assists yoga teachers and yoga therapists in creating and organizing yoga practices. It also features simple, informational articles on how to sequence yoga practices for maximum effectiveness. Olga strongly believes in the healing power of this ancient discipline on every level: physical, psychological, and spiritual. She strives to make yoga practices accessible to students of any age, physical ability and medical history specializing in helping her students relieve muscle aches and pains, manage stress and anxiety, and develop mental focus.

Resources

1. Hacking the Nervous System by Gaia Vince (Mosaic, the science of life) http://mosaicscience.com/story/hacking-nervous-system