How to Handle Challenging Yoga Student Behaviors

Article At A Glance

Every profession comes with its unique frustrations and challenging interpersonal dynamics. Teaching yoga is no exception. Challenges range from students skipping Relaxation Pose (Savasana) to being averse to using props to over-focusing on getting a hard “workout” from practice. The encouraging news is that handling challenging yoga student behaviors is a skill that we can get better at, just like we can improve our cueing or sequencing or hands-on assists.

We can then manage these challenging yoga student behaviors in ways that keep our classes welcoming and nurturing for our students. After all, the point is their safety, enhanced wellbeing, and growth. As much as challenging yoga student behaviors may get on our nerves, it’s not about us.

To learn more and get varied perspectives, I spoke with three experienced teachers about what student behaviors they find most challenging and how they react: with intention, care, and detachment.

Challenging Yoga Student Behavior #1: Doing a Personal Practice in a Group Class

Eva Christopherson (E-RYT 500)

“One behavior I find challenging in classes is when a student completely disregards my instruction and comes to class to practice their own thing,” shares Christopherson. She fully distinguishes that from modifying poses, not practicing certain poses that don’t currently make sense for their body (particularly in cases of working with an injury), and generally not pushing themselves past their own safe and reasonable limits. “Those are things I actually encourage my students to do in class!” she notes.

Instead, Christopherson is referring to practicing something completely different from what an instructor is offering, and which they have, most likely, very intentionally planned. For example, a student may do fast Sun Salutations (Surya Namaskar) with Handstands (Adho Mukha Vrksasana) when an instructor is leading Sun Salutations at a slower pace that focuses on subtle refinements of each pose in the sequence.

In other cases, yoga students could be working on things apart from building blocks that a teacher is laying out while working toward a peak pose. Not only does that potentially block an opportunity for the student to learn and grow in their practice, but it could also be a physical safety issue.

Christopherson describes another problem with students completely doing their own thing in class: “I find it to be distracting for the other students in the room, as well as myself, the teacher.” Additionally, students fully disregarding instruction can “cause confusion for other students and … disrupt the energy of the room,” she adds. Teachers have a responsibility to do all that they can to create the best possible experience for the class as a whole, and not just for one student in that class.

Stories From the Field: Handling Challenging Yoga Student Behaviors

Christopherson describes an instance that illustrates a lot of the above:

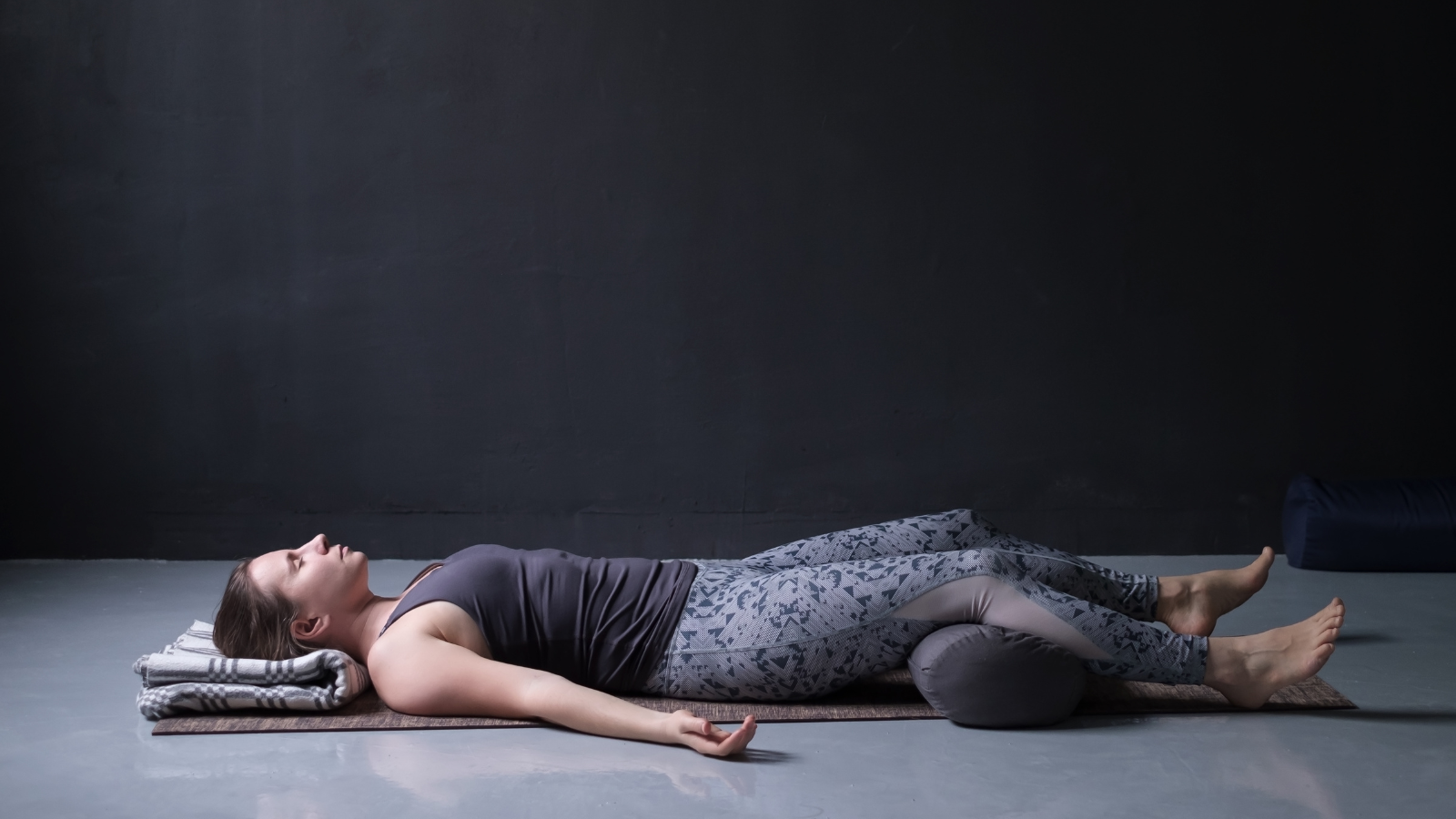

“There was one instance in which I had a student who was doing his own practice in my class and it was very disruptive. I was teaching a restorative class and the student was doing his own Vinyasa practice in the room and breathing quite loudly.

“I quietly went up to him while the other students were in Child’s Pose (Balasana), and asked if he could practice a bit more quietly because it was distracting the other students.

“While the student looked a bit startled that I spoke up to him, he did slow down his personal practice and joined the group in the class I was teaching. At that moment, I felt that it was important that I play the role of a teacher, while still showing compassion for the individual in front of me.”

Solutions That Christopherson Uses: Making Yoga Practice Welcoming

Remind the class that yoga is really about deepening our awareness so that we can more clearly see the impact of our actions—on ourselves and on others.

Ask the class to ask themselves, “Are you doing certain poses because that will bring you closer to balance (in mind, body, spirit) and wellbeing? Or are you doing them out of habit? That “encourages students to listen inwardly and learn how to trust the signals their body is giving them, not just what they think they should do,” Christopherson notes.

When it might be necessary to speak to a student individually, be sure to do so in a respectful and non-judgmental tone.

Challenging Yoga Student Behavior #2: Forcing Oneself Into the “Full” Expression of a Pose

Rachael Whitworth (E-RYT 500)

“I often see students trying to force their bodies into what they think might be the deepest expression of a pose, at the expense of spaciousness and expansiveness, leaving no room for the free flow of energy or breath,” explains Whitworth. That compromises the process of “creating space in the body while learning how to create space in the mental and energetic bodies through the vehicle of the breath,” she notes. This, to Whitworth, is a primary aim of asana practice.

This tendency to force—to pull, to scrunch, to strain—of course, has safety implications. Forcing can cause pulled muscles, overuse injuries, or even bigger issues such as fractures and dislocations. In a more energetic sense, there’s already enough striving and perfectionism in our 21st-century world. (I think many of us would agree.) Yoga can be a space where we can appreciate that where we are is enough—more than enough, even.

When we can guide our students toward this understanding, we can help them to be more intentional and accepting of whatever is within this present moment, on and off the mat. From there, practitioners can begin to “move more intentionally toward a life that feels more open and expansive. We allow ourselves the space to breathe, just as we learn to do through our yoga practice,” Whitworth affirms.

Stories From the Field: Finding More Space in Triangle Pose (Trikonasana)

Whitworth describes an example of how such striving plays out, and what she does to guide students back to finding ease, space, and full breath.

“In Triangle Pose, students will often try to reach for the floor or their big toe. This leads to a collapse through the upper body in the direction of the floor. They physically scrunch themselves up trying to get to that big toe.

“Here I guide them to lengthen their top arm up toward the ceiling, drawing their torso up as they do, activating the muscles of the core and expanding wide through the arms and chest. If the neck allows, the gaze lifts skyward, instead of focusing on the ground. The bottom hand might rest on a block, or perhaps it hangs freely inside the front leg. The entire energy of the pose shifts. Everything is moving up and out.

“This lengthening up and out away from the floor allows the torso to unwind from the downward-facing scrunch, and they can begin to tune into the lines of energy in the body—from the outer blade of the back foot through the crown of the head, and through the fingertips of each hand.

“We then focus the breath through these lines of energy, perhaps noticing how much more freely it flows in this more physically expansive shape.”

Solutions That Whitworth Uses: Make Your Own Yoga Practice

Encourage students to let go of what they think a pose “should” look like, and instead notice what it feels like for them. It’s about how it feels for them, not how it looks, and only they can know that.

Underscore and celebrate the uniqueness that each of us brings to yoga. “We each bring a unique body and energy to the mat, and there is beauty in that uniqueness,” Whitworth reminds us.

Emphasize finding a sense of expansiveness over any aesthetic of a pose. “This sense of expansiveness, when practiced regularly, begins to translate into a sense of spaciousness in the rest of our lives off the yoga mat,” she notes.

Encourage a pause between action and reaction. To Whitworth, that’s “where we begin to find freedom or liberation from suffering in our lives.” How? When “we find ourselves pausing from one moment to the next, aware of what is arising for us, [we give] ourselves the opportunity to choose how we react in the following moments,” she explains.

Challenging Yoga Student Behavior #3: It’s Also About How You Show Up

Renee LeBlanc

LeBlanc has certainly seen her fair share of strange student behavior, including (no joke) a student opening a bag of chips in class and proceeding to snack. “I honestly couldn’t believe it. It was so out of place that I just laughed and said, ‘Oh my God, you have to do that outside,’” she says. She’s dealt with phone attachments, and has come to “just ignore it.” Attachment to our phones is a force bigger than yoga teachers can take on alone!

To LeBlanc, stemming challenging yoga student behaviors comes with your presence, and the sense of experienced leadership that you bring to your teaching. “As you become more experienced, you’ll have better behavior in the room. It’s really hard during your first years of teaching. People can sense if you’re a little hesitant and a few people might take advantage of that,” she notes.

As Christopherson discussed with students completely disregarding practice, that used to really “distract and get to” LeBlanc, she recounts. She’s come to notice that happens because the student wants to be challenged more. In a mindful and safe manner that doesn’t detract from other students’ experiences, she’ll guide them there. As part of this process for her, she can pretty quickly tell “where they are and what they know” such as the style of yoga they’re trained in and what skills they have.

Addressing Challenging Yoga Student Behaviors: Remaining a Student and Growing as a Teacher

From there, all LeBlanc has to do is “give them a reason to listen to me: whether it’s an alignment cue or a variation that they might not be able to do yet. Then they start listening, and they love coming to class more.” She also encourages students to think about how they’re using their energy over the course of a class, to conserve it for more challenging poses and pose variations ahead.

The more you learn as a teacher and hone your skills—from your cueing to your sequencing to how you integrate philosophy—the more students “won’t want to miss what you’re saying and they won’t be distracted,” LeBlanc believes. She recommends “remaining a student” and “continuing to give valuable information” to your students to keep moving in that direction. This could include helping them hone alignment and learn new poses and skills.

On a positive note, LeBlanc reports that in her online teaching (where she’s teaching nowadays), students are “amazingly focused.” Though some yoga students can be difficult, yoga itself teaches us that we all have the tools within us to learn, grow, and evolve. With knowledge, intention, and a spirit of care, we yoga instructors can help our students move past challenging yoga student behaviors to get closer to their fuller and more grounded selves. That’s a meaningful way to serve and make the world just a bit more harmonious and easeful.

Also, read...

Warrior I Pose: 5 Strengthening Variations

Deepening Your Home Yoga Practice: An Interview with Judith Hanson Lasater

4 Easy Ways to Use a Sandbag in Yoga Practice

Related courses

Breath as Medicine: Yogic Breathing for Vital Aging

Yoga and Myofascial Release: Releasing Chronic Tension with the Bodymind Ballwork Method

Yoga and Detoxification: Tips for Stimulating Lymphatic Health

Kathryn Boland is an RCYT and R-DMT (Registered Dance/Movement Therapist). She is originally from Rhode Island, attended The George Washington University (Washington, DC) for an undergraduate degree in Dance (where she first encountered yoga), and Lesley University for an MA in Clinical Mental Health Counseling, Expressive Therapies: Dance/Movement Therapy. She has taught yoga to diverse populations in varied locations. As a dancer, she has always loved to keep moving and flowing in practicing more active Vinyasa-style forms. Her interests have recently evolved to include Yin and therapeutic yoga, and aligning those forms with Laban Movement Analysis to serve the needs of various groups (such as Alzheimer’s Disease patients, children diagnosed with ADHD, PTSD-afflicted veterans – all of which are demographically expanding). She believes in finding the opportunity within every adversity, and doing all that she can to help others live with a bit more breath and flow!